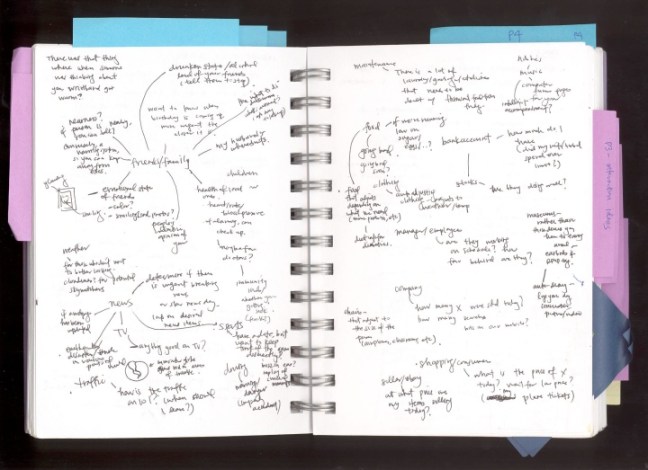

I’ve been writing songs since I was approximately 8 or 9 years old. At that time, I would carry a notebook with me in my guitar case or in my pocket, and if I felt inspired, I would write lyrics or compositional notes (chord progressions/charts/etc.) inside that notebook. I brought that notebook with me to school, to band practice, to basketball games, to family parties… In short, I brought it with me everywhere!

When I got into high school, I got my first cell phone. Instead of using the notebook, I began texting myself lyrics. I would pull up a blank text message, input my own cell phone number, type any lyrics I was drafting at the time, and hit send. This served as an ongoing record or database of lyrics for me. When phones become more advanced, I started using note-taking applications to document lyrics and I would use the phone’s audio/visual technology to record the actual music while I played my guitar or hummed/whistled the melody. As a doctoral student endeavoring through my dissertation, I continued to use cell phone applications such as the Google Drive/Docs and Evernote to document or audio record ideas for exploration or inclusion in my drafts.

Now, in my profession as an educator, I’ve regressed back to using the traditional notebook. I’ve done so for a few reasons. Writing notes using pen and paper (the research I’ve read deals with students using pen and paper to take notes vs. using a computer to take notes during classroom instruction) allows the note taker to retain information better. In addition, I use a highlighter to highlight notes (or aspects of certain notes) that I’ve implemented/accomplished, which allows me to better visualize progress I’ve made over a certain period of time. I call this notebook my “Idea Log.”

Over break, I always take some time to peruse my Idea Log and reflect on the highlighted portions. These highlighted portions help me visualize the things I’ve tried/changed/implemented/achieved/etc. The following is a brief list of ideas I’ve tried or implemented this school year so far (quoted verbatim from my Idea Log):

- “Utilize a Contact Journal to keep note of who I’ve spoken with and which classrooms I’ve seen. Take notes in the journal and follow through when someone needs support with something.

- “Make positive phone calls home to the parents of my teachers. Try starting or ending the week with this strategy.”

- “Create a ‘What Are You Learning Today? A Visit from Dr. E.’ shared document. Share the Google Form/Office 365 One Note with staff members so they can edit the document in real time and share the wonderful things happening in their classrooms that they would like me to see/observe.”

- “Use Animoto to make monthly videos of the happenings in the school and share through social media channels.”

- “Find an interesting and timely ‘Article of the Week’ and share through email. Encourage staff to share their own and continue through our journey of professional learning.”

Looking through the Idea Log, I am also reminded of a few other ideas I’d like to try this coming semester.

How do you record your ideas? What have you done or accomplished this year and how do you keep track of your progress?

Like/Comment/Share!